Purpose-Led Digital Transformation: Why Change So Often Turns Into Chaos

Vikram Korde

Vikram has extensive experience as a global marketing leader in well-known blue-chip FMCG companies leading billion-dollar brands and innovation-driven retail organizations. His philosophy to deliver results : Be Agile, Be customer-obsessed, Follow the evidence & Be creative

Executive Summary

Most digital transformations fail not because of technology, but because the organisation never agrees on why it is changing. When purpose is unclear, platforms multiply, priorities fragment, and people disengage.

This article argues that purpose-led digital transformation starts by surfacing consequences early—especially those affecting people and processes before decisions harden. Leaders who anchor change in a clear cause, and test operating models deliberately, replace expensive chaos with informed choice and durable progress.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Most organisations don’t fail at purpose-led digital transformation because they lack technology, money, or ambition. They fail because no one ever really stops to ask why they are doing it, and even when they do, the answer rarely lands with enough clarity to guide decisions.

As a result, companies launch programmes, buy platforms, hire consultants, and run town halls. On the surface, progress appears to be happening. Beneath it, however, something else is unfolding.

Slowly and almost imperceptibly, what was meant to be transformation turns into confusion, fatigue, and cost. There is activity everywhere, yet progress is hard to find. Motion replaces direction. What emerges is not transformation, but expensive chaos.

This is not a fringe issue. In fact, it sits at the heart of why so many digital and organisational transformations stall, underdeliver, or quietly fade away.

The Comfort of Activity

Spend enough time in boardrooms and a familiar pattern appears. The language of transformation sounds confident and assured: digital ambition, AI-first strategies, next-generation operating models, data-driven cultures. Everyone seems aligned. The slides are immaculate.

However, when a simple question is asked—why are we doing this, really?—the answers begin to drift.

Some point to competitors. Others mention board expectations. A few refer to available technology or the need to modernise. None of these explanations constitute a cause. They are reactions, and reactions are a weak foundation for change.

MIT Sloan has been describing this dynamic for years. Organisations fall into what it calls the technology trap, mistaking tools for strategy. Technology, after all, only amplifies intent. When intent is vague or fragmented, amplification simply accelerates confusion.

Without clarity of purpose, transformation becomes choreography. There is noise, motion, and urgency, but no shared direction. Inevitably, choreography without direction collapses into chaos.

Purpose-Led Digital Transformation Starts Somewhere Else

The transformations that actually work tend to begin in a very different place.

Consider Microsoft under Satya Nadella. The turnaround did not start with Azure or artificial intelligence. Instead, it began with a cultural reset. The organisation moved from “know-it-all” to “learn-it-all,” from internal competition to collaboration, and from defending legacy to embracing curiosity.

Only then did technology follow. Purpose came first.

Adobe’s shift from packaged software to a subscription model followed a similar logic. The move was not driven by tools. It was driven by a clear intent: predictable revenue, continuous customer value, and faster innovation cycles. Because that intent was explicit, the organisational pain that followed—new incentives, new skills, new metrics—was absorbed rather than resisted.

In both cases, technology mattered. Crucially, it mattered after the cause was clear.

Where Digital Transformations Usually Go Wrong

Most failed transformations begin with a platform decision quietly presented as strategy.

A bank invests heavily in a new core system, yet no one can clearly explain which customer problems it will solve. A retailer launches an omni-channel initiative while stores, inventory, and incentives remain misaligned. A manufacturer deploys advanced analytics without changing who has the authority to decide.

In each case, the pattern is the same. Technology moves faster than people and processes. The organisation only discovers the real consequences once everything is already in motion—when reversing course is painful and trust is thin.

Ford’s abandoned digital overhaul and GE Digital’s short-lived rise were not failures of capability. They were failures of clarity. The cause was never strong enough to hold the organisation together once pressure arrived.

Leadership Is the Real Constraint

Across Harvard, MIT, and INSEAD, research has converged on a consistent conclusion: transformation is not primarily a technology challenge. It is a leadership one.

Leaders who succeed do not begin by asking what to deploy. Instead, they start by being brutally clear about the problem they are trying to solve. They speak in plain language. They resist abstraction. Most importantly, they understand that transformation reshapes identities, power structures, and daily routines, not just systems.

DBS Bank in Singapore offers a useful example. The ambition was not to “be digital.” It was to remove customer friction. Everything else followed from that decision. Technology became an enabler rather than the objective. As a result, DBS is now recognised as one of the world’s most advanced digital banks, not because of its stack, but because of its coherence.

Culture Is Not Soft. It Is Structural.

One of the most persistent misconceptions in transformation is the belief that culture will sort itself out once new systems go live. It will not. Culture is infrastructure.

Unilever’s transformation under Paul Polman worked because the purpose of long-term value creation linked to sustainability was clear and credible. That purpose shaped decisions across strategy, talent, innovation, and digital investment. Technology reinforced the culture. It did not attempt to replace it.

LEGO’s recovery followed a similar path. The turnaround was not driven by tools, but by a renewed commitment to creativity, design thinking, and customer focus. Only later did technology amplify what already existed.

Seeing Consequences Before It Is Too Late

A recurring problem in digital transformation is timing. Organisations often discover the real impact of change, especially on people and processes only after decisions have hardened.

By then, resistance has formed. Costs have escalated. Options have narrowed.

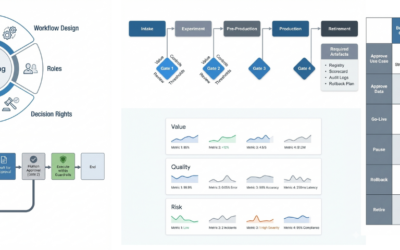

This is precisely why approaches that surface consequences early matter. Not to predict everything, but to see enough. When used properly, digital twins allow leaders to stress-test operating models, decision flows, and behavioural assumptions without putting the real organisation at risk.

Combined with deliberately small, intentional disruptions, what we refer to as controlled detonations, this shifts transformation from hopeful intent to informed choice. Leaders stop guessing how the organisation will behave and start seeing it.

People and Process Always Decide the Outcome

Technology does not transform organisations. People do. And people do not change because a platform goes live. They change when incentives shift, roles evolve, and expectations become clear.

Domino’s Pizza understood this instinctively. The goal was never “digital transformation.” It was to make ordering pizza effortless. That clarity reshaped processes, decisions, and accountability. Technology simply made the outcome possible.

Maersk’s reinvention followed the same logic. The cause was simplifying global trade aligned teams across geographies and functions. As a result, technology reinforced the operating model rather than fragmenting it.

The Cost of Losing the Cause

When purpose-led digital transformation is absent, the symptoms are familiar:

- Different parts of the organisation interpret the change in different ways

- Technology investments outpace organisational readiness

- Fatigue and cynicism quietly take hold

- Costs rise faster than impact

- Old behaviours resurface once attention moves elsewhere

These are not execution failures. They are clarity failures.

Direction, Not Projects

Organisations that endure do not treat transformation as a programme with a start and end date. Instead, they treat it as a directional choice about how they want to operate, decide, and adapt over time.

Purpose matters because it aligns decisions when trade-offs appear. It provides coherence when priorities clash. And it creates continuity when tools, vendors, and management fashions inevitably change.

Transformation without a cause is not bold or visionary. It is simply expensive chaos. Purpose-led digital transformation, by contrast, becomes something else entirely: a disciplined way of reshaping how an organisation thinks, works, and competes over time.

That difference is not subtle.

It is the difference between motion and progress.

Other Reading

Harvard Business Review

Anchor text: research from Harvard Business Review

Link: Digital Transformation is Not about technology

MIT Sloan Management Review

Anchor text: MIT Sloan Management Review highlights

Link: Why Digital Transformations Fail

Operating Model for AI: The Hybrid (Human + AI) Teams Blueprint.

Saket’s focus is on helping organisations to become flexible and adaptive, while emphasising that people in the organisation grow as well. His experience includes working with a range of organisations from large, complex global enterprises to small entrepreneurial...

Why Auditable, Human-Governed AI Agents Matter Now

Learn why AI agents must be auditable and governed. Discover how leading enterprises are evolving their operating models for AI at scale.

Importance of Managing the Change and Also Leading It

Current business environment demands we manage and lead the change. Learn how Versatile Consulting supports its clients with Whole-Scale Change methodology. It combines rigorous management, shared vision, and real-time leadership to drive sustainable transformation.